This is how British historian Eric J. Hobsbawm describes the period 1914-1945. Is a full-scale war possible, given what happened today between Russia and Ukraine? Highlighting certain parallels between the current period and this catastrophic era is tantalizing, in the current context.

The decline of Great Britain in the late 19th centurye century and the rise of new powers – the United States, Germany, Japan – led to two world wars to determine which one will play the role of hegemon. Today, according to some, the decline of the United States and the rise of China and India, as well as Russia’s return after decades of decline, put us in a dangerous situation.

The United States does not accept the new multipolar reality (the existence of at least three major competing powers), while China, Russia and others increasingly oppose the hegemony that Washington seeks to maintain. Throughout history, transitions from one hegemony to another have tended to lead to major wars.

- Hear his interview on Richard Martineau’s show which airs live daily at 9:05 a.m. through QUB-radio :

Democratic decline

The 1920s and 1930s were marked by the decline of democracy with the emergence of fascism, Nazism and other types of dictatorships (Franco in Spain, Salazar in Portugal, etc.), in the context of an economic crisis that was still unprecedented. Today, in a less dramatic list – at least for now – we must note the rise of radical rights in developed countries. On the citizen side, opinion polls show a decrease in attachment to democratic values.

In the United States, a major world power, democracy is clearly in crisis, as demonstrated by the attack on Capitol Hill and the refusal of millions of people to accept the results of the presidential election. To this must be added new phenomena: environmental catastrophe with the loss of thousands of living species, resource depletion and climate change. Hard times are ahead.

World War?

Should we fear a new world war? Here, the greatest caution must be exercised. History doesn’t always repeat itself, and certainly not in the same way. Russia was much weaker economically than Germany, then Europe’s leading industrial power. He had neither the means – we saw them on the ground – nor the intention to conquer Europe.

However, the war between Russia and NATO through Ukraine remains fraught with danger. Nuclear weapons did not exist in the era of the catastrophe, except at the end of 1945. In that year, only one country that had them, the United States, also used them. Russia today will have about 6,000 nuclear warheads. The more the Ukrainian army gains territory, the greater the risk of desperate measures on the part of the Russian authorities. It’s not for nothing that Biden’s speeches against Putin have become more “diplomatic” lately.

We also know that Russian and American army staff are in constant contact to avoid the worst. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account the internal realities of Russia. Since 2014, Putin has had nothing left to offer his people in terms of economic and social progress. Its popularity also began to decline before the war. The fragility of his regime drives him into a spiral where we can be pulled more directly than we already are.

However, we must not forget that political life is not a matter of mechanics or natural laws, but of the will of actors and citizens: reversals are always possible and generally unpredictable.

As much as the rise of the radical right can counter new political orientations that will lose them support, the Russian people can rise against Vladimir Putin’s regime. This also applies to the people of China and the United States. A new catastrophic era, while possible, is not necessarily inevitable.

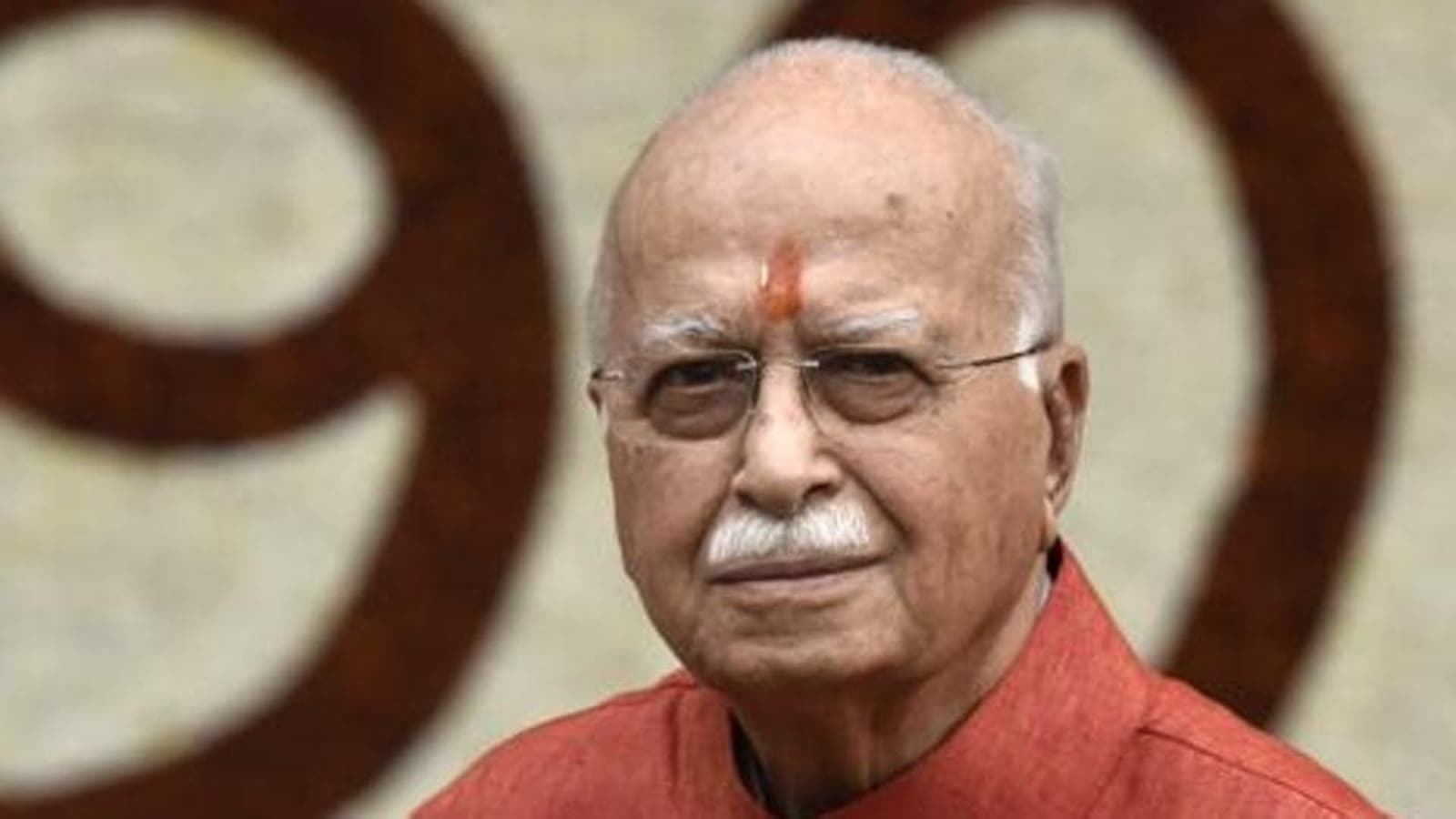

Michel Roche, professor of political science and specialist in Russia at the University of Quebec in Chicoutimi

“Award-winning travel lover. Coffee specialist. Zombie guru. Twitter fan. Friendly social media nerd. Music fanatic.”